Whole Class Lessons: The Most Efficient, Least Effective Form of Instruction

Kathy Collins and I were co-teaching a summer workshop for teachers on how to teach reading effectively. We were sharing about different kinds of direct instruction—various ways we can teach students the skills, strategies, and mindsets they need to be effective readers, and Kathy said something that I’ve been thinking about ever since. She was making the case for keeping whole class lessons short—for keeping mini-lessons mini. “After all,” she said, “whole class lessons are the most efficient but least effective form of instruction.”

Whoa. Let’s step back and consider this for a bit…and not just in reading. This is advice that applies to just about any subject area at any grade level.

Whole Class Lessons Are Efficient

No doubt, lessons taught to the entire class are efficient. We’re able to deliver information, strategies, and instruction to everyone, all at the same time.

This is important. If we’re all working on character analysis or long division or understanding the three branches of the US government, there’s information that everyone needs to know. Gathering the class together for some whole-class instruction is a great way to do that. There’s also a sense of community that comes from being together with others as you learn, and that’s important to the cohesion of a class.

So Why Are They Not Effective?

There are some problems with teaching the whole class the same thing at the same time in the same way, though. Have you seen any of these challenges?

- Some students already know what you’re teaching. They quickly get bored and tune out.

- Some students are quickly overwhelmed by what you’re teaching. They get confused and lost and either tune out or flare up.

- Attention spans are short. There’s a reason TED talks are capped at 20 minutes. Even highly intellectual and engaged learners can only stay focused for a limited amount of time.

- One students’ dysregulation tanks the lesson for everyone. It only takes one (but it’s so much worse with more) student to have a meltdown (which can be caused by being bored and/or overwhelmed, by the way) to disrupt learning for everyone. You now have two unappealing options: forge ahead through the disruptions, knowing other kids aren’t learning or shut the lesson down, which again means other kids aren’t learning.

- These are just a few common problems…ones I often see as I coach and support teachers in K-12 classrooms. I’m sure you can think of others…

What Are More Effective (But Less Efficient) Forms of Instruction?

Our teaching can be more effective (though less efficient) when we work with fewer students at once. Two strategies are especially effective.

Strategy Groups: Let’s say there are some kids who are struggling with long division. Their number sense is still weak, and they aren’t understanding what happens when a number is broken into equal sized parts. Pull a few at a time together at a table and bring out the base ten blocks. You can now model a few problems for students using blocks. You can adjust your examples based on numbers these particular students can handle.

Individual Conferences: The most targeted—probably the most effective yet least efficient—form of instruction is a one-on-one conference. When you work with one student a time, you can make your instruction specific to what that student needs. You can use examples that you know will resonate and engage in more back-and-forth dialogue about what makes sense and what the student is struggling with.

Of course, these two strategies are impossible to get to if our whole class teaching takes up the whole class period, so we should consider some ideas for…

How to Shorten Whole Class Instruction

There are a bunch of ways we might keep whole class teaching tight. Some are simply about managing time effectively. We might set a timer to remind us when 8 minutes has passed—so we can wrap lessons in under 10 minutes. There are more fundamental changes we might consider as well. Here are four strategies you might find especially helpful.

1. Avoid the Q&A Style of Instruction

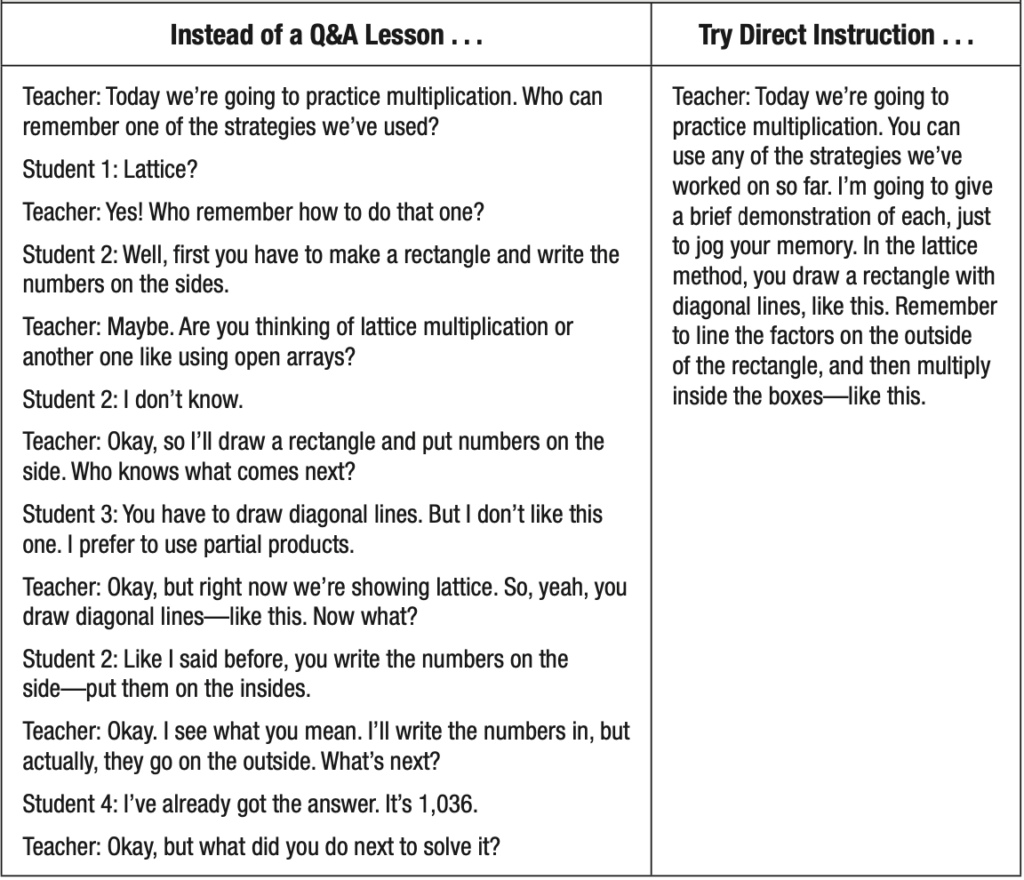

In an effort to include student voice in lessons, sometimes we try to “teach” a lesson by asking questions and having students answer them—effectively dragging content out of the students. It’s almost always messy and leads to unclear teaching. Kids try to answer questions but invariably don’t do so with nice tidy correct answers, so we try to deftly maneuver around their attempts to get back on track. It also takes way too much time. Instead, let’s be direct and clear with instruction so we can get to students’ application and practice of learning more quickly.

Here’s an example of the Q&A style of teaching and it’s more direct counterpart from What We Say and How We Say It Matter: Teacher Talk that Improves Student Learning and Behavior.

2. Stop Teaching Before Everyone Is Clear About What to Do

Almost always, when we teach a whole class lesson, some kids already know what we’re teaching and many more understand after hearing the content and/or directions once. There will also always be a few who need more time and a few more passes before they understand what to do. Instead of keeping all students in the whole class lesson while you try to gain everyone’s understanding, release students to the active application portion of the class period. You can then invite students who need more instruction to stay with you for a bit more teaching, or you can pull them into a strategy group or coach them individually once they’re working.

3. Have One Clear Teaching Point Per Lesson

Another way to keep lessons short is to have one main teaching point or one specific goal per lesson. Perhaps students are about to revise a piece of writing. You could share a few ideas for them to try, let students choose the one they think will best connect with their draft, and let them get to it. If you feel like the class also needs some instruction about how to have a solid ending, you might bring them all back together after they’ve been writing for 20 minutes for another short lesson. Not only will this keep whole class instruction short, but it may also provide a brief break from work that can reenergize students so they can keep revising for the rest of the period.

4. Don’t Spend Time Correcting Work as a Class

Let’s say that students had a homework assignment or an in-class assignment that you want to go over—something simple and straightforward like a set of math problems or science questions. You want students to correct their own assignments, both so they can see where they were on-track (and where they were off) and to save time so you don’t need to correct them all.

Though this isn’t technically a direct-teaching lesson, it’s still a common time-suck in classrooms that we could greatly reduce. Instead of going over the problems one at a time (especially by having students volunteer what they think the right answers are—which puts them in jeopardy of being corrected in front of their peers), give students an answer sheet and let them correct their work individually. You could then create small groups strategy sessions to review problems that students struggled with.

To be clear, whole-class instruction is important, and we shouldn’t ditch it all together. There’s a place for efficiency. If we can keep it short, however, we’ll save more time for strategies that may be less efficient but are so much more effective.

Author

-

Mike Anderson has been an educator for many years. A public school teacher for 15 years, he has also taught preschool, coached swim teams, and taught university graduate level classes. He now works as a consultant providing professional learning for teachers throughout the US and beyond. In 2004, Mike was awarded a national Milken Educator Award, and in 2005 he was a finalist for NH Teacher of the Year. In 2020, he was awarded the Outstanding Educational Leader Award by NHASCD for his work as a consultant. A best-selling author, Mike has written ten books about great teaching and learning. His latest book is Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher. When not working, Mike can be found hanging with his family, tending his perennial gardens, and searching for new running routes around his home in Durham, NH.

You may also like

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference

- October 23, 2024

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog

Feeling Burned Out? Maybe It’s Time for a Shake-Up!

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Comments

Love this article and I would add that if you read the last line( “we’ll save more time for strategies that may be less efficient but are so much more effective.”) and really think about that sentence, it becomes very apparent how inefficient efficiency is in education. All learners have individual learning schemata, get to know your students and teach the individuals. The class as a whole will be better for it.

I love this article, and I completely agree that whole-class lessons can be efficient in delivering information to all students at once. However, as your post points out, there are also some downsides to this approach. Some students may already know the material, while others may struggle to keep up. Furthermore, disruptions from one student can derail the entire lesson for everyone.

I appreciate the suggestion to use alternative teaching strategies, such as strategy groups and individual conferences, to target specific student needs. These may be less efficient, but they are more effective in meeting the diverse needs of students.

I also agree with the idea of having one clear teaching point per lesson. This not only keeps the lesson shorter but also allows students to focus on a specific skill or concept. Instead of trying to cram multiple objectives into one lesson, it would be more beneficial to break them up into smaller, more focused lessons. It is important to avoid spending time correcting work as a class. As your post suggests, giving answer sheets and allowing students to correct their own work not only saves time but also promotes self-reflection and accountability.

I believe that while whole-class lessons have their place, we should also strive to incorporate more targeted and individualized instruction to meet the diverse needs of our students.