Inequities Hidden in Plain Sight: Traditional Grading Practices

Is there a more controversial issue in schools right now than grading? If it’s not at the top of the list, it’s certainly close. As many schools move away from traditional grading practices and toward standards-based (proficiency-based or competency-based) ones, teachers, parents, and kids are confused. While it’s not the goal of this article to delve deeply into this subject, readers might be interested to know that we fully support this shift. The move toward reporting students’ understanding of content and proficiency with skills instead of how they rank against each other is a good one. It’s heartening to see that many colleges and universities are being clear that this change will not hurt students’ abilities to get into their schools. Both of us have spent more than a decade writing narrative, content proficiency-based reports for students who have gone on to successful middle, high school, and college careers.

Though this trend has a lot of momentum, there are still many traditional grading practices in place in schools. It is our contention that these practices especially disadvantage children who experience poverty. (As an important reminder, in the introduction to this series, we are clear. Not all children who live in poverty are disadvantaged, and a middle or upper-class family setting does not ensure stability.)

Traditional Grading Practices to Reconsider

- Bonus Points for Non-Academic Reasons: When teachers offer academic bonus points for students who bring in boxes of tissues or for remembering to place their phones in the phone hotel as they enter class, what’s the message that’s sent to kids who can’t afford to buy supplies or who don’t have a phone? Even if the points offered are minimal and don’t really impact a final grade, a clear message is being sent. Some kids have an academic advantage because they have an economic one.

- Grading Homework: Since we’ve already explored the inequities created by homework in another post, we’ll simply reiterate here. If kids from poverty have a harder time doing homework, then grading it further deepens the damage. Factors out of a student’s control shouldn’t impact them negatively.

- Comparative Grading: Anytime we base grades, even in part, according to how well kids do as compared with each other, we invite inequities. Few teachers actually still grade using a bell curve, but some related practices are still quite common: scaling tests and creating tests that are intentionally difficult are two. Instead, let’s use assessments that show whether or not kids mastered learning, and celebrate if they can all meet standards (and reteach when they don’t).

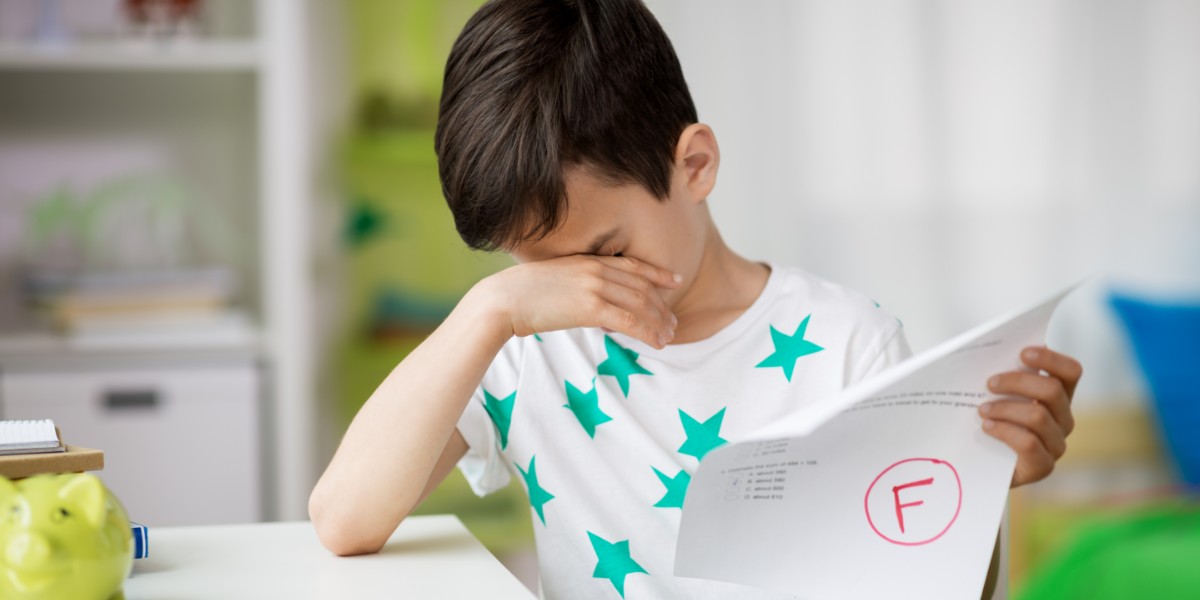

- Giving Zeros, Taking Points Off for Late Work, Averaging Grades: All of these common traditional grading practices tend to focus more on compliance to teacher demands than they do mastery of content or skills. They also make it hard for kids to recover from a rough week or two—when chaotic lives interrupt learning. Instead, let’s assess whether kids learned the content or mastered skills, not how quickly or how compliantly they did so.

- Not Allowing Redos or Retakes: There are some who consider redos and retakes to be a softening of grading. Actually, it’s quite the reverse. By allowing students to go back and try again, we give them the opportunity to learn from mistakes and gain success after failure. (This is, by the way, just like many situations outside of school. You can fail your driver’s test and the Bar exam over and over and still pass in the end). Perseverance is an important social/emotional skill for students to learn and practice. Especially for students whose lives may be more turbulent, second chances are so important!

- Leaving Remediation Up to Families: Is it common in your school for some families to hire tutors to help kids understand content or do well on assessments? Are some families given quiet hints that extra help might be needed outside of school? If so, there may be an unspoken (or whispered) rule in play for families. If you have the means, you can pay to help your child get better grades. In a school where comparative grading is present, inequities become even more pronounced. Again, we find ourselves wondering why factors out of children’s control (this time socioeconomic status) should impact them. They should not. They must not.

Many traditional grading practices often put students from poverty further behind in schools. When a student’s success is contingent upon them having academic support systems outside of school, we put a significant number of our most vulnerable at a disadvantage. These students are often made to feel inadequate and incapable of managing seemingly insurmountable odds. The result is feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, which have the potential to lead to challenging behaviors and academic disengagement. The cycle becomes perpetual as these counterproductive behaviors lead students to get bad grades and continue to fall further behind.

Many traditional grading practices often put students from poverty further behind in schools. When a student’s success is contingent upon them having academic support systems outside of school, we put a significant number of our most vulnerable at a disadvantage. These students are often made to feel inadequate and incapable of managing seemingly insurmountable odds. The result is feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, which have the potential to lead to challenging behaviors and academic disengagement. The cycle becomes perpetual as these counterproductive behaviors lead students to get bad grades and continue to fall further behind.

What to Do Instead

Another traditional grading practice to reconsider is relying primarily on tests as assessments. So, let’s play with this one a bit and see if we can do better. Imagine that you’ve just received an edict from administration. You may no longer use tests or quizzes to assess student learning. How else would you find out what kids know and what they can do? We’ve used this thought experiment with high school teachers several times. After a few moments of disorientation, ideas start flowing fast and furious. Here are a few that we have heard:

- Confer with students to assess understanding

- Use projects (slide shows, movies, board games, art projects, songs, write children’s books etc.)

- Allow students to choose assessments that they think will help them demonstrate their learning

- Have students self-assess more

- Use learning journals

- Observe students as they work and take notes to record what they know and still need to work on

- Have students give presentations to the class

- Have students make lists of common misconceptions or mistakes and explain why they’re wrong

What else can you come up with? How else might you assess student learning that actually focuses on the learning? What assessment practices can you put in place that allow all kids a fair shot demonstrating mastery? Let’s continue the conversation!

(To connect with other educators who are rethinking assessment in schools, check out the Teachers Throwing Out Grades Facebook group. They are lively and supportive educators who share tons of practical ideas!)

Read about more inequities common in many schools in our other posts in this series!

Inequities Hidden in Plain Sight (Common School Practices that Disadvantage the Already Disadvantaged)