Should Teachers Call Students “Friends”?

What do you think–should teachers call students “friends”?

Educators at William H. Rowe School in Yarmouth, Maine are engaged in an exploration of teacher-talk. They’re using What We Say and How We Say It Matter: Teacher Talk that Improves Student Learning and Behavior as a book study book. They recently wrote to me with this question, and it’s one that I have heard many times from teachers—especially in the primary grades. Here’s their detailed question and my response (shared with their permission, of course!):

We are a K/1 school and many of us use the word “friend” when referring to a student (especially if we don’t know their name) or to a group of students (“Good morning friends,” as a class walks down the hall to their class). Of course, as rule followers, we all wanted more clarification and understanding as to why we should rethink our use of this label. Should teachers call students “friends”? Any insight you can provide would be so helpful as we dive deeper into what we say and how we say it!

This is a really common language habit…especially used with younger children. I guess I’d start by encouraging people not to change this habit too quickly. As you said, teachers (especially in the primary grades!) tend to be rule-followers, but I would hate for people to change how they talk simply because I suggest it (or because they think they’re supposed to). Instead, teachers should decide which language habits they want to work on based on their positive beliefs–and their desire to bring their language closer to their best intentions.

All that being said, here are a few reasons to (potentially) reconsider calling children “friends.”

As you said, some people might do it because they don’t know children’s names. If this is the case, using “friends” (or sweetie, honey, ma’am, sir, etc.) doesn’t help adults learn kids’ names. In fact, these substitutes can actually decrease our chances of learning them. (The longer we go without knowing kids’ names, the more embarrassing it becomes to ask.) Instead, let’s take the time and effort to learn students’ names, even if they’re not in our particular classroom.

Another reason to reconsider it is that it isn’t accurate. Children aren’t our friends. We should certainly treat children with friendliness, but that’s not the same thing. More often, I hear teachers justify the use of this term by saying that they want kids to consider each other friends. This is certainly well-intentioned. We want everyone to treat each other with kindness and respect, and we would certainly try and ensure that all kids feel like they have several friends in the class. But do we really have a goal of having all 20-30 kids truly be friends with each other? Probably not.

Perhaps the most important reason (from my perspective) is as much about the tone that’s used (and the climate that may be created) when teachers call students “friends.” It’s often said with a sing-song voice, and this may make it feel condescending (although that’s never the intention!). In her book, What Every Kindergarten Teacher Needs to Know (NEFC, 2011), Margaret Wilson hits this point head-on. She recommends: “Talk to kindergarteners using the same tone and cadence you would use with adults. Talking in a sing-song cadence or high pitched tone can give the impression that we see kindergarteners as pets or as incompetent people” (p. 66).

Here’s a question that might help see this question through a new light. At what age would it no longer feel appropriate to use this term with a group of students? Would we call high school students “friends” when addressing our Calculus class? How about with middle school students? How about 5th graders? 4th? 3rd? At what point do we feel that it’s age-appropriate to use this term, and why? At what age would it sound like we’re “talking down” to children? If it would feel that way for 6th or 4th graders, why might we not feel that way with 1st graders? And again…what’s our goal? Do we want children to feel like they’re strong and competent–like they have a sense of agency and power? Let’s make sure that the way we talk helps foster the culture and climate we’re trying to create.

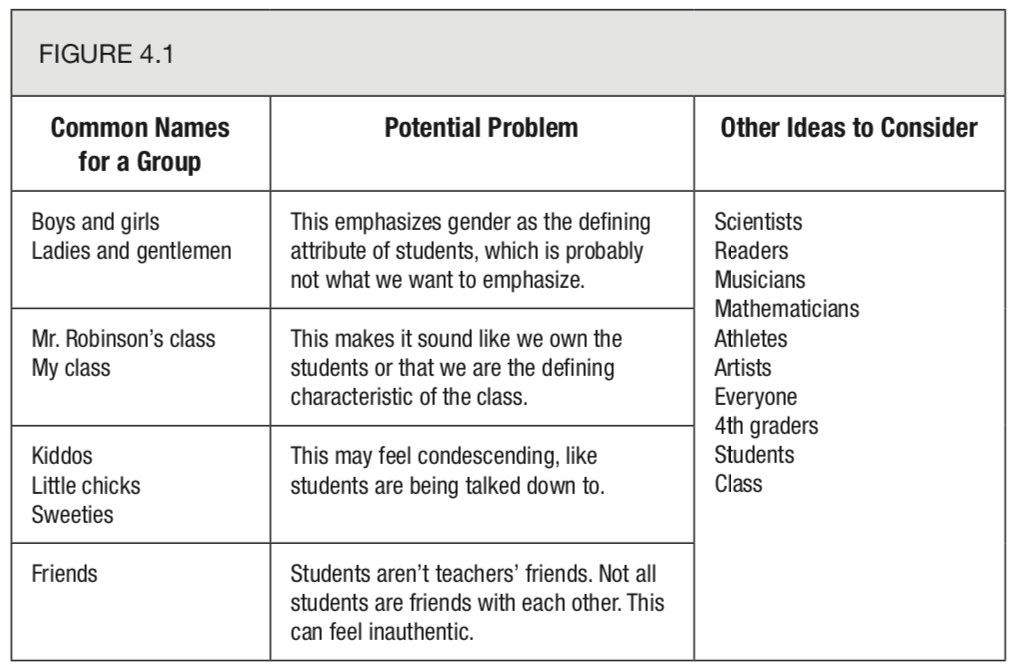

So, if we are going to reconsider this term, what might we use instead? The following chart, pulled from p. 37 of Chapter 4 (Develop Students’ Positive Identity) of What We Say and How We Say It Matter, offers some suggestions.

Again…don’t change your language because I think it’s a good idea. I certainly want to push people’s thinking–and I hope to push people to reconsider language habits and then think for themselves. The last chapter of the book offers lots of practical strategies for shifting language patterns, and one of the most important pieces of advice I offer is to take time to develop a commitment to a language change before you start to try and shift anything.

I hope this fuels some interesting discussions and deep thinking! I’m so glad you’re all enjoying the book and having some cool discussions!

For more blog posts about the way we use language in schools, click here. If you’re interested in facilitating your own book group with this book, here’s a study guide you can use.