Shifting from Extrinsic to Intrinsic Motivation

It might be the understatement of the summer that teachers, students, parents, and administrators are anxious about the upcoming school year.

In addition to the priorities of health, safety, and equity of access to education in this COVID-19 period, distance learning also presents a number of challenges for student engagement. In just these last few months, there is already evidence of student disengagement.

For teachers of electives—courses not considered “required”—student disengagement presents a particular concern. I am an instrumental music teacher, and like many of my colleagues who teach electives, I question whether students will choose to actively participate or even enroll in our courses during this challenging time. If they cannot play in group performances, use school equipment, or participate in other co-curricular activities, will engagement in these classes decline disproportionately?

Regardless of discipline or grade level, a key question always facing educators, and acutely now during the COVID era, is: how can I keep students engaged? In my own thinking, experience, and research, I’ve landed on intrinsic motivation as central to addressing this question, whether we are teaching in a classroom or by video from our homes.

Two Kinds of Motivation: What vs. Why

There are many factors currently playing a role in student disengagement, but motivation is one that teachers can powerfully influence through curriculum design.

In his book Drive, Daniel Pink examines two kinds of motivation. Extrinsic motivators fixate on the what, like grades, performances, or tests. He argues that extrinsic motivators lead to drawbacks such as short-term mindsets, stymied creativity or adaptivity, limited performance, and deterred intrinsic motivation. In contrast, intrinsic motivators focus on the why of “why does what I learn/teach matter?” and lead to empowerment, independence, creativity, and collaboration.

When intrinsic motivation—the why—is front and center, it is much more likely that students will view learning experiences as enjoyable, valuable, and relevant to their lives.

When intrinsic motivation—the why—is front and center, it is much more likely that students will view learning experiences as enjoyable, valuable, and relevant to their lives.

-David Davis Tweet

Shifting Thinking from What to Why

It can be easy to default to extrinsic motivation in teaching. I’ll admit that, in the past, I often relied on extrinsic motivators, and sometimes still do. As I tried to keep students practicing or enrolling in my elective program year after year, it was all too easy to turn to prizes, stickers, or “easy” participation grades. I’ve even found that special events like concerts or competitions can fall prey to a “teach to the test” mentality, where directors or coaches focus student attention on external valuations rather than internal values.

When I began to realize that my answer to “why we teach music” was not “to give stellar concerts,” but rather, “to empower young people to be independent thinkers, explore their identities, and collaborate with peers to reimagine and revitalize their learning,” I started to shift my tactics to promote intrinsic motivation.

Examples to Promote Intrinsic Motivation

After much reading and experimentation, my curriculum looks wildly different than it did just a few years ago. The below examples come from a music classroom, but the framework of intrinsic motivation—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—applies to any classroom.

Autonomy (Student Choice) |

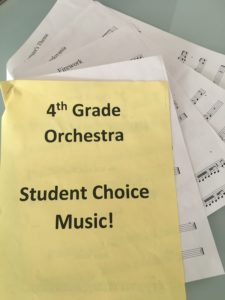

I used to: choose all the music for concert programs myself. The external motivator was “to receive a reward or good grade, you need to learn this specific literature because I believe it is quality literature.” |

|

Examples:

|

Competence (Skill Development over Content Covered) |

I used to: assign workbook pages purely sequentially. The external motivator was “how many pages/songs can you complete by the end of the year?” and was rewarded with achievement prizes and grades. The students with few rewards or low grades often quit, probably thinking “music isn’t for me.” Grades reflected factors such as behavior, whether students remembered to bring their instruments to class, or if they participated in concerts. |

Now: I use the workbook as a resource, not as the course curriculum. I’ll have a lesson plan prepared, but will often begin by asking students to identify skills they are curious to learn. If our ideas are not similar, we will co-design an assignment that builds that skill, rather than squash their inquisitiveness for the sake of covering my content. Instead of using prizes or grades to judge student ability—assessment being done to students—I assess with them through guided self-reflections. I work to ensure that grades communicate academic and musical skill growth, not nonacademic factors that distort the truth about student achievements. |

Examples:

|

Relatedness (A Sense of Belonging) |

I used to: consider myself as a “Maestro”; I trained students to regard quality performance technique as the primary goal of my class. I would utilize only pre-composed repertoire in the classical music style. Students were required to choose from a list of allowable instruments. The external motivator was “you have to work because the concert is approaching and you don’t want to embarrass the group (or me!).” If students couldn’t keep up, or didn’t enjoy the prescribed instrument options or musical selections, they often became frustrated and disengaged. Some even quit. |

Now: I view my role as a supportive mentor whose purpose is to help students see themselves as uniquely musically creative and able to grow, regardless of how the ensemble sounds. Students of any ability and background are actively welcomed and encouraged to join. Repertoire now includes student selections, compositions and improvisations, as well as interdisciplinary collaborations; the diversity of artistic activity and output is greatly increased and reflective of the students themselves. The format of performances sometimes looks nothing like a typical concert. I may give advice, but ultimately students shape their musical identity by choosing to study any instrument they want. (One year I had an accordion player in the band!) In the past couple years, no student has dropped my class partway through the year, and in fact enrollment and retention has increased. |

Examples:

|

Barriers to Making the Shift

It can be scary or discomforting making major changes to a time-tested curriculum. Change can be messy and uncertain. Before I implemented my new approach, I was concerned that the quality of students’ musical output would plummet, parents or administrators might be critical of non-traditional methods, or that I wouldn’t have enough time to plan new projects or accommodate student choice. In my experience, I can attest that investing in intrinsic motivation was worth all the effort and vulnerability.

The Results

Greater intrinsic motivation resulted in students practicing more voluntarily, so technical skills accelerated. Although it took hours of extra planning up front, my teaching actually became more efficient and manageable over time as students began learning greater independence and problem-solving skills. My program has seen significant growth in enrollment and retention, and receives strong support from parents and administrators.

Of course, I still have room to grow, and nothing I’ve shared hasn’t been done or said before, but I hope by sharing these examples it might spark new ideas for others that will lead to meaningful student engagement. Especially if distance learning continues, we should continue to brainstorm and share ways to provide students with autonomy, skill development, and a sense of belonging so that they are inspired to engage with their own educational journey.

Author

-

David Davis is an instrumental music teacher with experience in elementary, middle, and high schools. He currently teaches at Clear Springs Elementary School in Minnetonka, Minnesota. He is also a district innovation coach who helps educators address barriers, collaborate to find creative solutions, embrace new mindsets, and evoke a passion for change. His progressive approach has been featured on NBC News Washington. In addition to teaching, David is a performing saxophonist and vocalist in the Twin Cities. You can connect with him on LinkedIn or Facebook.

- Share:

You may also like

The Perfect Breakfast for Teachers

- February 11, 2025

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference

Now:

Now: