Without These Three Conditions, Student Choice Probably Won’t Work

“If I give my students choice, I’m worried they’re going to make bad choices,” I often hear teachers say. “They’re just going to choose the easiest option. Or, they’re going to choose what their friends choose.”

There’s no doubt that sometimes students will make poor choices. They might choose a math option that’s too easy or a book that’s too hard. They might pick a topic to learn about because they’re following their friend’s lead. Sometimes kids will base their choices on what they think their teacher wants them to do. I’ve even had some kids beg, “Would you please just tell me what I should do?!”

There’s no doubt that sometimes students will make poor choices. They might choose a math option that’s too easy or a book that’s too hard. They might pick a topic to learn about because they’re following their friend’s lead. Sometimes kids will base their choices on what they think their teacher wants them to do. I’ve even had some kids beg, “Would you please just tell me what I should do?!”

Learning to make good choices is hard, and part of our work as facilitators of student learning is to help kids get better and better at making good choices. In addition to giving students direct instruction and supportive coaching about how to make good learning choices, there are also three conditions we should nurture to help boost students’ ability to choose well.

As I was working on the final draft of Learning to Choose, Choosing to Learn, I half-jokingly told an editor that the section about these three conditions should be titled, If You Don’t Do These Things, Don’t Even Bother Giving Kids Choice. The half of me that was joking understood that such a negative title would be a turn-off to some readers. The other half was actually pretty serious. There are some pretty common practices in schools that can impede students’ willingness and ability to make good choices—ones that have personal relevance and that are appropriately challenging.

Do you want to give kids more choices about their learning? If you’re not setting these three conditions, student choice probably won’t work.

1. Create a Safe and Supportive Environment

Consider the emotional risk required of real learning. You have to take a deep breath and be willing to stretch and grow. You have to allow yourself to be in a place where you’re not sure if you can be successful. When we ask students to “make a good choice” as a learner, we’re asking them to place themselves in this risky place. This can be especially challenging for students who come to school each day already on the edge of fight, flight, or freeze–students who are struggling to hold themselves together every minute of the day. Of course, no teacher sets out to create an unsafe learning environment—I think we all want kids to feel safe and supported in schools.

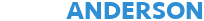

However, there are some common mistakes made in schools that we should know about and avoid:

|

Want Your Students to Make Good Choices? Create Safe and Supportive Environments |

|

| Instead of… |

Consider… |

| Discipline systems that emphasize punishments and rewards | Discipline systems that emphasize skill-building and relationships |

| Judgmental praise that sets a competitive tone in the classroom (“I love the way Sarah is ready to go!”) | Supportive language that sets a tone of collaboration and self-reflection (“It looks like some people are ready to go.”) |

| Classrooms where all students face forward—sending the message that the teacher is the focus | Classrooms that are flexible and collaborative—allowing for lots of student interaction |

| Using competition to excite and motivate students | Offering competition as an option for students who find it a helpful learning tool |

| Telling students to get along with each other | Teach students skills of collaboration and cooperation |

2. Boost Student Ownership

Offering students choices about their work is a great way to boost student ownership of learning, but what if kids don’t feel any ownership to begin with? Or, as is more likely the case, what if they’ve lost their sense of ownership and drive as they’ve progressed through school? What if students feel like they’re doing your work instead of theirs? Especially in school districts that have adopted scripted curricula, discipline systems that reward compliance and obedience, and grading practices that emphasize working for grades (instead of using grades to reflect learning), kids can learn to navigate these systems by becoming good little worker bees—focused on teacher-pleasing or working for treats or grades. (Of course, many kids in these systems cope in other ways—like rebelling or disengaging entirely.)

Here are some strategies to consider to help boost student ownership of learning:

|

Want Your Students to Make Good Choices? Boost Student Ownership of Learning |

|

| Instead of… |

Consider… |

| Classroom displays that are teacher-centric | Displaying lots of student work |

| Using teacher-centric language (“I’m going to give you three choices about…”) | Using student-centric language (“Here are three choices for you to consider…”) |

| Relying on incentives and rewards to motivate students | Facilitating great work that allows students to experience and practice self-motivation |

| Assessment and grading that are overly emphasized and controlled by teachers | Assessment and grading systems co-created with students to support learning |

3. Teach Student How to Learn

We might say to students, “Think about yourself as a learner. Which of these three math choices is the best one for you?” But what if kids haven’t yet learned how to “think about themselves as learners”? It’s up to us to teach them how to do this! This requires us to slow the typically frenetic pace of school. Instead of jumping from activity to activity—keeping kids so busy their heads are spinning—we need to take some time to teach students how to really think. They need to practice skills of reflection and metacognition so they can make truly informed and thoughtful choices about their learning.

Here are some ways we can help students get better at making good choices:

|

Want Your Students to Make Good Choices? Teach Them How to Learn |

|

|

Instead of… |

Consider… |

| Assuming students know how to think about their own thinking | Teach habits of mind that students need to fully engage as learners |

| Showing choices and then having students choose | Having students slow down and think about choices before they make them |

| Maximizing work time and skipping student reflection | Having students reflect on their learning and choices as (and after) they work |

| Using language that focuses on talent, intelligence, or gifts (“You’re such a great writer!”) | Using language that emphasizes a growth mindset (“Your writing skills have really grown this year!”) |

Do you want to learn more about these three conditions? I recommend checking out Chapters 2, 3, and 4 of Learning to Choose, Choosing to Learn. You’ll find lots of practical advice to help you facilitate student choice well!