As Students Return to School, Don’t Focus on SEL or Academics: Do Both

As schools welcome more and more students back through their doors, we’re all trying to figure out the best way to do so. It seems as though there are two wildly different needs we must address. As I talk with school leaders and teachers, and as I read education news stories, I worry that we may take one of two dramatically different (and both counterproductive) paths.

Mistake #1: Focus on Learning Loss

The first mistake would be to freak out about “learning loss” (a term I can’t stand, by the way). No doubt, academic learning hasn’t been the same over the past year, and many students have had dramatically less time in school and time doing schoolwork. We may reasonably assume that they haven’t learned as much academic content as they would have otherwise.

What are schools in this camp likely to do? Double-down on rote academic learning. Fueled by companies that are eager to profit from our panic, schools may purchase programs that promise fancy metrics, personalized dashboards, and quick-fix solutions to help get kids “caught up.” These efforts will likely focus on school, district, or even state-wide data, and that data will likely come from standardized assessments. Since rote skills are easier to assess via standardized assessments, schools will then focus on these rote skills. In an effort to “catch kids up,” kids may spend huge amounts of time plugged into skill-based computer programs and/or filling in drill-and-kill worksheets. They’ll be grouped by ability and placed in small groups working on skills in isolation.

And what will the upshot of all of all of this be? Just as kids most need to feel safety and belonging—to be known and heard and loved—they’ll likely feel an increased sense of anxiety and isolation. They will also receive the message, loud and clear, that they’re behind (or even further behind, as the case may be). Feeling incompetent and disconnected from others, they’re likely either panic or give up, neither of which will help them learn.

Mistake #2: Focus Solely on Community Building

One might think that the first ideas sounds horrible, so the reverse must be the way to go. We’ve been in a global pandemic, after all—is it really important that everyone be caught up on math facts or have read The Red Badge of Courage? In a well-intentioned move to support students’ mental health and social-emotional learning, schools may decide that it’s time to put academics away for a while and focus singularly on building a sense of inclusion and community.

What might this look like? Schools will tell teachers to help kids get to know each other and to feel safe before they begin their academic work together. Kids will play games, engage in numerous “ice-breaker” and “community building” activities, and spend time sharing and making personal connections with each other. Though teachers already know and use many of these activities, they’ll likely invest tons of time and energy (and schools might, of course, purchase kits) coming up with these activities, conflicted as they understand the importance of belonging, safety, and fun but worry about even more academic time slipping by. Some schools may encourage teachers to spend time helping kids process their feelings about the pandemic—helping them cope with the emotional toll they’ve experienced.

While a few community-building games and icebreakers might be fine, there are some downsides here as well. If you’ve ever been in a professional development workshop that uses too many icebreakers, you know how quickly they get old. They’re exhausting, and after a while, you start to wonder, “Are we ever getting to the actual content?” Kids also tire of these, and for many students, these can actually feel too risky—increasing students’ anxiety and leading some to shut down and others to act out. Especially students who have suffered mightily during the pandemic—ones who have lost family members or whose families have lost jobs or homes—might not want to share about this with others. School is some kids’ safe place because if offers an oasis from chaotic home lives. Teachers, likely feeling uneasy on ground that feels like the counselor’s real estate, may avoid these talks or worry that they’re bumbling their way through them, resurfacing trauma and making things worse.

Both of these approaches are clearly flawed. To focus solely on academic work, especially the rote kind that’s easy to package in a program and assess on a test, is to neglect the important work of helping students reacclimate to school and reconnect with their peers. (Besides, if there was some magic strategy that could somehow help kids “catch up” quickly with academic work, wouldn’t we know about it, and wouldn’t we have already been doing it?) But we also shouldn’t neglect the academic work at hand. After all, we’re in schools, so what kinds of communities are we building if not academic ones, and how could we possibly do that without academics?

Instead: Build Communities of Learners

Instead, let’s help build academic communities. Let’s create safe and supportive groups of students who feel a sense of belonging and connection and do so through engaging in fun and meaningful academics. Let’s support social and emotional learning by helping kids gain the skills they need to do this great work. At the same time, let’s get to know our students well, figure out what they can do, and then build off of their strengths, differentiating learning so that all students can experience the joy of appropriate academic challenge and growth.

Below are four examples to illustrate how this might look. In each of these, let’s assume that these are units that teachers were already going to teach. Hopefully they’re specific enough to offer some concrete ideas but general enough so you can see how these same kinds of structures could be used with many different content areas.

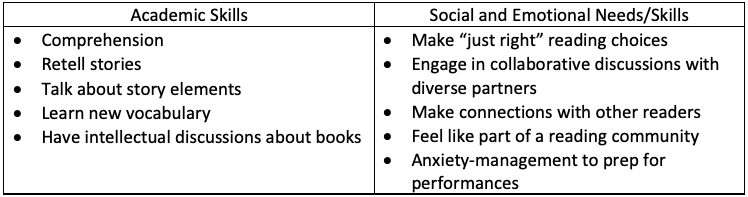

Primary Grades: Fairytales and Folktales

For several weeks, students will be immersed in fairytales and folktales as they explore, compare, and contrast these two genres. They’ll have many shared experiences through whole class and small group read-alouds as well as short videos and movies. In reading workshop, they’ll read a variety of books and stories on their own. This will allow for rich differentiation, both through varied text complexities as well as individual reading conferences with the teacher. Students will share stories with each other, both through reading conferences and through a class bulletin board where they can recommend books. During writing workshop, students will try writing their own fairytales or folktales. As a culminating event, students will get to choose a story to act out with a small group—either through a puppet show or a readers’ theatre.

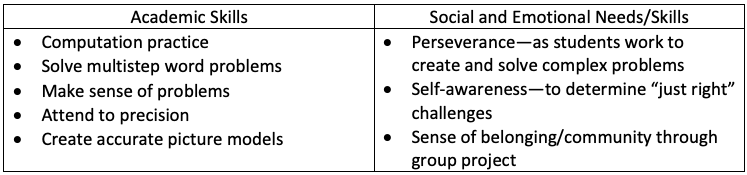

Middle Elementary Grades: Computation and Story Problems

Students in the middle elementary grades are working to master the key computational skills of adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing. During this unit, they will get to create and solve their own problems. While the teacher teaches brief whole class lessons and facilitates many small group sessions, students will draft, revise, and edit a variety of story problems. The ultimate goal will be to create a book of story problems (with an answer key in the back!) to be published as a class. Since students will each create their own problems, this work will be individualized for each learner as they are encouraged to create and solve “just right” math problems. Individual conferences will allow the teacher to differentiate instruction according to the needs of each student. Adding illustrations and picture models to the stories will both add an artistic flair to the book and will deepen conceptual understandings. In the end, all students will receive several copies of the book so they can have one at home, use one in class (as a math choice activity), and give another away to a friend or family member.

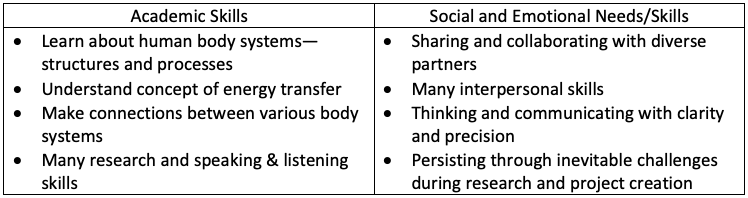

Middle School: Human Body Systems

Students will each choose one human body system to study. Through an independent research project, students will learn about the structure and function of the system they chose as well as explore how energy transfer works in that system. Throughout this project, students will work together—asking each other questions, pushing each other’s thinking, and supporting each other’s learning. For example, one day, students will spend ten minutes in partnerships with people studying different systems. Their challenge will be to complete a Venn diagram together to show similarities and differences between the systems. As a culminating event, students will put together projects (models, slideshows, video animations, posters, etc.) to teach others what they have learned. Presentations will be shared with the class and with families.

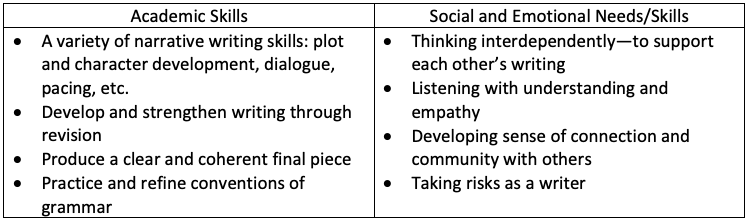

High School: Short Story Writing

In this writing workshop genre study, students will explore short story composition. Students will first read a variety of short stories, examining key literary features. They will then respond to many (many!) varied quick write invitations—some about personal experiences while others are fictional. Students will finally pick one (or more) stories to develop. They will write individually but confer with other students to support each other. The teacher will confer with students to individualize and differentiate instruction—meeting each writer where they are. In the end, the class will publish an anthology of short stories—which will be available through print and ebook formats. Students will decide on and help plan a celebration event to mark the completion of the project.

Conclusion: The New Normal

So, as we consider how to best bring students back to school, let’s work toward a blended approach. Instead of focusing solely on supporting academic learning or creating safe and supportive communities, let’s do both. And then, let’s make this the new normal. After all, isn’t this what a great school experience should look and feel like all of the time?

Author

-

Mike Anderson has been an educator for many years. A public school teacher for 15 years, he has also taught preschool, coached swim teams, and taught university graduate level classes. He now works as a consultant providing professional learning for teachers throughout the US and beyond. In 2004, Mike was awarded a national Milken Educator Award, and in 2005 he was a finalist for NH Teacher of the Year. In 2020, he was awarded the Outstanding Educational Leader Award by NHASCD for his work as a consultant. A best-selling author, Mike has written ten books about great teaching and learning. His latest book is Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher. When not working, Mike can be found hanging with his family, tending his perennial gardens, and searching for new running routes around his home in Durham, NH.

You may also like

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference

- October 23, 2024

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog