Classroom Management 101: A Refresher

You may think of the first weeks of school as a time to focus on classroom management, and it is. But in fact, all year long, we should consider classroom management an active part of our daily teaching. How do we set students up for success with a learning activity? Which routines are running smoothly and which need some tweaking or revisiting? Are the class rules we created in the fall still being referred to daily–to guide students in their work and interactions? In this article, we’ll consider a few important practices we can use all year. Let’s call this a refresher: Classroom Management 101.

Teachers Notice Good Classroom Management

Here’s what’s got me thinking about this.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been teaching demonstration lessons in classrooms in several schools. Some have been to demonstrate student choice and intrinsic motivation in action. Some have been to help teachers learn how to observe in each other’s classrooms and give each other non-judgmental feedback.

No matter what the main goal of the lesson is, there are some common teacher reflections that keep popping up in debrief sessions. They sound like this:

“When you had kids generate ideas for how to talk well together in partner chats, kids knew just what to do, and their partner chats were on-topic and respectful.”

“When you called students up to the circle area by birth month, it helped the transition be safe and smooth.”

“I noticed that when you had kids refer to our rules before you played the game, it helped them stay in-control and kept the math game running smoothly.”

“You moved around the group as they worked, listening to students’ thinking and helping them stay focused.”

“I noticed that as soon as some students started to get a little too silly, you paused the activity and had kids reflect on how things were going. You had them focus on positives, and that kept the tone of the class positive. Then they were able to start again successfully.”

Even though the goal of these lesson wasn’t to demonstrate effective classroom management, it’s something teachers notice. Good management leads to smooth lessons and more learning.

Here are a few classroom management components to check in on. How are each of these going in your own practice?

Rules

You might call rules by another name: expectations, a classroom constitution or contract, goals, norms, etc. Regardless of what you call them, you and your students need them. You couldn’t play basketball or Monopoly without a set of rules to guide your play. The same goes for learning activities. How could kids work together in math or have reading/writing conferences without shared expectations for how to interact effectively? If you didn’t create rules with your students at the beginning of the year, it’s not too late. Go ahead and do it now!

Good rules are simple, easy to remember, and few in number. Avoid long lists of procedures (walk on the right side of the hallway, plug in laptops when you’re finished,) or rules that sound negative or harsh (no fighting, no swearing). Instead make sure rules are positive and focus on what to do (be kind and respectful, take care of our classroom, work hard and have fun).

Keep rules posted where they’re easy to see and easy refer to. And refer to them often! They should guide all that you do in your classroom. Before kids are going to listen to class research presentations, have partners chat about the class rules. Which might especially help audience members be respectful? Before playing a science review round of Jeopardy, have a few students share about how the game should look, sound, and feel, using the rules as a guide.

A benefit of referring to the rules often is that you center them as the anchor of discipline in the room, not you. Kids should give thoughtful and kind feedback in a writing conference because that’s one way they can live up to the spirit of their rules—not because you want them to. You can actually reduce power struggles with students (especially ones who can be oppositional) when appropriate behavior is guided by class rules instead of your own personal expectations.

Routines

There are dozens of routines students need to know. There are academic ones like having a partner chat, logging into their student account, signing up for a teacher writing conference, and using approved websites for research. There are also non-academic ones like moving between classrooms and lunch and bathroom procedures.

At the beginning of the year, you (hopefully!) modeled and practiced these routines—directly teaching students how to maneuver through the school day. The more time you invest in this explicit instruction, the better students can self-manage throughout the year.

Like plants in a garden, routines need tending. You can’t just plant tomatoes in early summer and expect them to yield fruit in August. Weeds crop up. Some weeks are dry, and they’ll need extra watering. So too, routines need maintenance. Kids need reminders about routines so they can stay on track. As the year goes on, some routines need adjusting as kids change and learning objectives get more complex.

Here’s a thought exercise you might try, either alone or with colleagues. Make a list of all of the daily routines students are expected to navigate. There are a ton. Try picturing yourself as a student walking into school in the morning. What should they know how to do? Are they supposed to enter through a certain door, walk on a certain side of the hall, go directly to a specific classroom, use a certain volume of voice? What’s next? How should they enter a room? What routines follow? Go through a whole day like this and write down every routine you can think of.

Next, rate each of these routines according to how well most kids are doing. Which ones are rock solid? Which are shaky? Which are a complete mess? Use this list to target routines to adjust and/or reteach. This will likely require an investment of time, but you’ll save time in the long run when the day runs so much more smoothly!

Realistic Expectations

Sometimes we, the adults in a school, create misbehavior by having expectations that are unrealistically high or that are out of step with students’ development. For example, it’s probably not realistic to expect students to walk in hallways without talking—a surprisingly common elementary school expectation. We know it’s unrealistic because adults can’t do it. This is just one of many.

Maybe it’s not realistic to expect students to sit on a hard cold tile floor for a 45-minute assembly (while adults sit in chairs around the perimeter of the room). Maybe it’s not realistic to expect 7th graders to be self-directed in a WIN block (often a modified study hall) at the very end of the day—after they’ve worked hard and been directed by others all day long. It’s probably not realistic to expect students to behave as well with a guest teacher as they do when we’re in the room.

Sometimes expectations may even be out of line with child development. Young children’s eyes can’t focus up close and then far away repeatedly. Having them copy information off of a board is really hard. Twelve-year-olds are going to talk—a lot. Asking them to listen to 20 straight minutes of direct instruction without talking is to invite off-topic side-conversations.

You’ll be able to tell when expectations aren’t reasonable when lots of kids struggle with them over and over. It might be time to adjust. Have kids talk quietly as they walk in hallways and have them bring chairs to sit in for assemblies. Put an independent work time earlier in the day when kids can be more productive. Keep direct teaching short so kids can interact and have more time for work. Give students activities they can handle independently when you’re going to be away from the room and someone else is in charge. Set your students up for success.

Self-Management Strategies

One of the most important components of classroom management is teaching students skills and strategies of self-management. After all, if the whole year is only going to be about you managing your students, you’re in for a long haul. The more you can help them learn to self-manage, the better!

For example, let’s say you want students to be able to play a fun academic game without getting too wild or silly. Are there certain strategies you might suggest they use (taking a few breaths to calm down, trying some self-talk, etc.)? Or, perhaps you could have your students share some ideas for how to stay in control but still have fun playing the game.

In just about every aspect of school, there are opportunities to help kids practice self-management. They might need to practice managing frustration while working with others or managing anxiety during a quiz. They likely need strategies for impulse control and self-control while working with others and participating in academics throughout the day.

We need to go beyond telling kids to be in control (or respectful or kind or…). We need to teach them how to do these things.

If you’re interested, here’s a short video of me helping third graders consider strategies for how to manage their interactions with each other as they engage in partner chats during a reading activity:

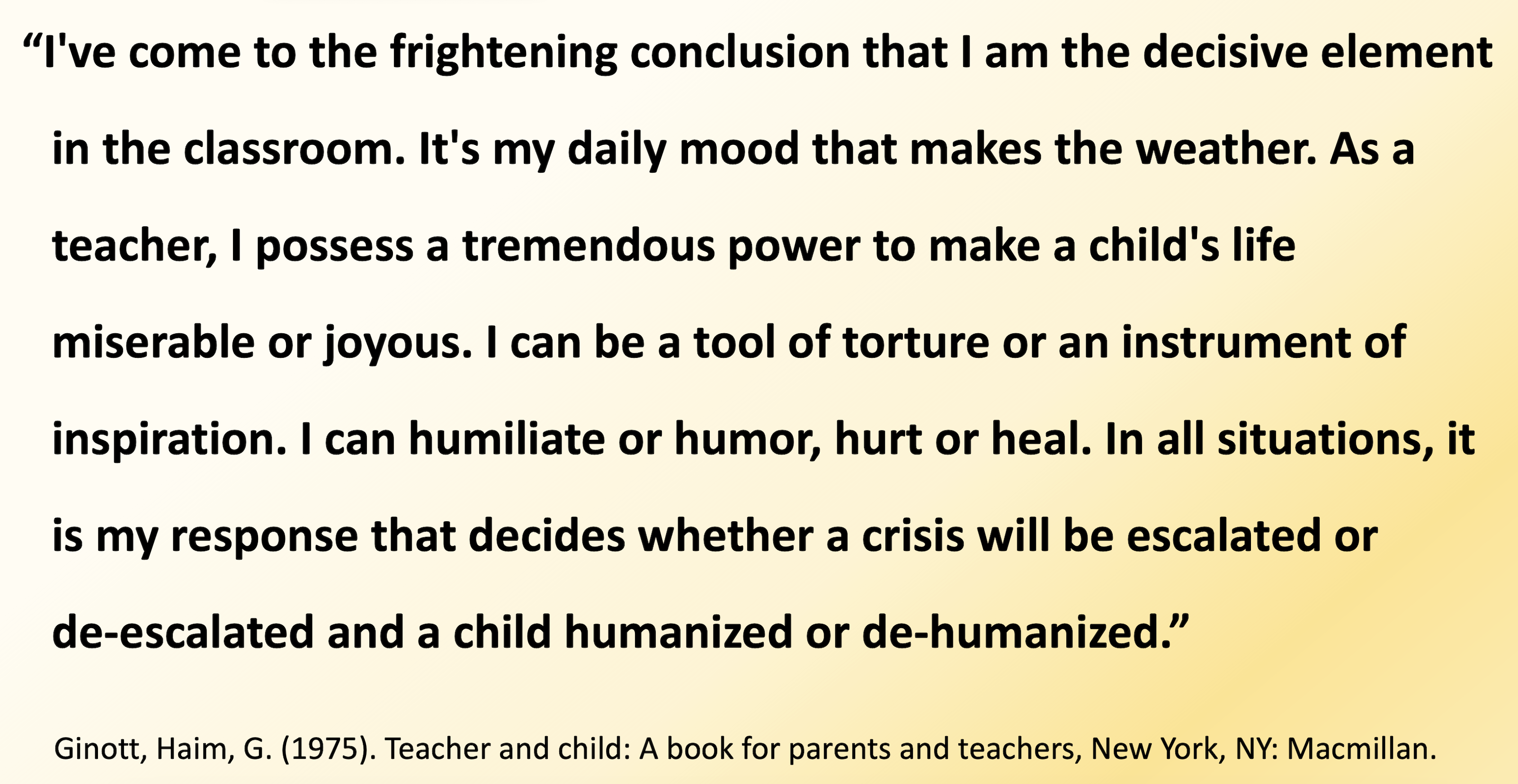

Signals for Attention

One routine in particular can make or break a day. How do you get the attention of the class so you can give directions, shift gears, or help students refocus? Is this signal (or perhaps you use multiple signals?) clear, consistent, and respectful? Does it work?

If you’re not sure whether or not a signal is respectful, consider this question. How would it feel if it was used with you at a staff meeting or in a PD workshop? Imagine you are in a deep discussion with a colleague about an important topic, and the facilitator called out “1-2-3, eyes on me!” and you were supposed to immediately—mid-sentence—call back “1-2, eyes on you!”? Would this feel respectful, or would you feel annoyed that you were cut off? Might you be tempted to lean back in and keep talking to your colleague so you could finish your thought? If a signal would feel disrespectful to use with adults, it’s worth reconsidering as a signal used with kids.

Whichever signals you use, make sure to teach them, practice them, reinforce them, and be careful you yourself are following through on how they’re supposed to work. For example, if you’re supposed to raise your hand and wait for everyone to be listening before you speak, be careful you don’t start talking when only half of the kids are ready. This kind of inconsistency can be confusing for students and often leads to signals falling apart.

Positioning and Proximity

A class is watching a brief science video, and two students are chatting in the back of the room. Their teacher quietly walks back toward the students and catches their eye. They stop talking. Their teacher stays next to them for a couple of minutes to help them stay on task.

Dismissal in a school of 900 K-6 students could be chaotic, but in this school, it’s calm and safe. All available teachers and staff stand in hallways as children are dismissed. They give kids high-fives, wish them a good afternoon, and engage in friendly banter. Their presence helps students remember to walk and move in an orderly fashion.

In these two examples, we see the power of positioning and proximity. Our physical presence can be a subtle yet powerful management tool.

If you’re working with a reading group and the rest of the class should be working independently, position yourself so you can easily see the rest of the class as you work with the group. If you’re supervising the lunchroom, walk around the room as kids eat, pausing as needed near potential hotspots. At an assembly, where kids are supposed to be respectful audience members, put yourself next to students who will need extra help staying in control.

Clear Limits and Respectful Consequences

I once heard someone say that some kids test limits because they need to know what the limits are. They push a limit to see what happens. Deep down, they’re hoping we’ll be firm, clear, and fair, and make them stop. That’s how they feel safe. (I heard someone else once say that some kids need this kind of information more than others. Some kids are “aggressive researchers.”)

If we’ve said that students need to walk in the halls and someone is running, we can say, “Stop, Mike. Go back and try that again. Walk in the halls.” A students knocks a potted plant onto the floor (either through fooling around or not paying attention). They should clean up the mess and repot the plant. If a student is shoving kids on the playground, they might need to take a break from the playground (or from the trouble spot where the shoving is happening) for a while. Two students chose to sit together and are fooling around instead of working. They should be split up so they can refocus on work.

In her positive and practical book, Positive Discipline, Jane Nelson suggests four criteria for logical consequences. They should be related to the behavior, respectful of the student, reasonable for the student to carry out, and (when possible) revealed in advance. Used without shaming or blaming students, logical consequences provide an effective alternative to punishments, which often manage in the short term but lead to defiance and resentment in the long term.

For a nuanced look at how to use consequences effectively across a school, consider checking out this article: Getting Consistent with Consequences.

Teacher as Model

A wise former colleague of mine was fond of saying, “Remember that as teachers we’re always modeling. Little people watch big people to figure out how to be big people.”

For better or worse, we’re always modeling.

How do you welcome students in the morning or when they first walk into class? Are you setting a friendly and welcoming tone by smiling and greeting students by name? Do you say, “please” when you’re asking someone to do you a favor and “thank you” when they do? How do you react when a student makes a behavior mistake? Are you patient and kind or sarcastic and snippy? (Check out this devastatingly honest reflection of how one teacher realized he was accidentally modeling mistreating a student: What Teaching Matthew Taught Me.)

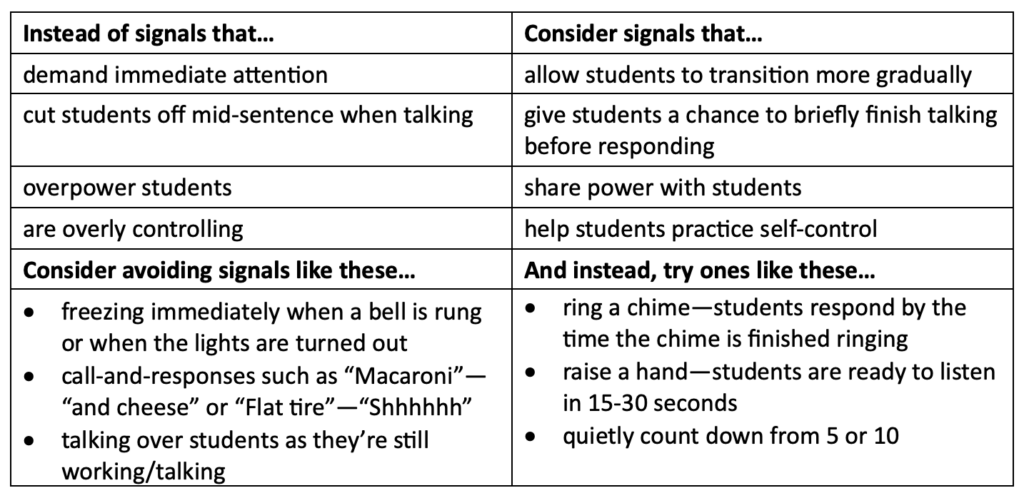

In short, are you modeling the kinds of behaviors you want your students to exhibit? Let’s not forget the power we have to set the tone of the classroom. You’ve perhaps seen this incredible quote which captures this idea:

Classroom Management 101: Take-Aways

So as you consider these core classroom management take-aways, what seems especially important? What might you try tomorrow? Remember, good classroom management helps kids learn more, and it’s part of our on-going everyday work all year long.

Author

-

Mike Anderson has been an educator for many years. A public school teacher for 15 years, he has also taught preschool, coached swim teams, and taught university graduate level classes. He now works as a consultant providing professional learning for teachers throughout the US and beyond. In 2004, Mike was awarded a national Milken Educator Award, and in 2005 he was a finalist for NH Teacher of the Year. In 2020, he was awarded the Outstanding Educational Leader Award by NHASCD for his work as a consultant. A best-selling author, Mike has written ten books about great teaching and learning. His latest book is Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher. When not working, Mike can be found hanging with his family, tending his perennial gardens, and searching for new running routes around his home in Durham, NH.

You may also like

Feeling Burned Out? Maybe It’s Time for a Shake-Up!

- July 12, 2024

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog