What About Kids Who Just Don’t Care?

“What about kids who just don’t care?”

When I’m supporting teachers in schools, either around classroom management and discipline or academic engagement and motivation, this is a question that often comes up.

We all know these kids, don’t we? They shut down quickly—often looking sullen or angry when faced with a challenging academic task. Or they seem so disengaged right from the start—before we’ve even had a chance to explain the lesson or activity we’ve worked hard to create. Their heads are on their desk. Their hoods are over their heads. Their eyes are half closed. Sometimes they even say—in no uncertain terms—“This is dumb. I don’t care.”

So, what do we do about kids who seem to not care?

I Don’t Believe Them

I don’t believe Dylan when he says he didn’t throw that rock. I don’t believe him when he says he wasn’t cheating in the math game, even though the three other students he was playing with contend that he was. So why would I believe him during writing when he scowls and says, “I don’t care about writing. It’s stupid!”

If he didn’t care, he wouldn’t be so angry—on the verge of tears, even.

If you gave students like Dylan a magic wand, and all they had to do was tap their own head to be successful, don’t you think they would? They might wait until no one was looking to save face, but of course they’d do it. In my experience, kids want to do well (even when they show otherwise). I’m with Ross Greene—kids do well if they can.

This makes the whole situation that much more heartbreaking. Our students really do care, but they seem to be their own worst enemies. Their negative energy shuts down any chance they have of learning or being successful. So why might kids say they don’t care if they do? And what can we do to help these kids?

Why They Shut Down

There are many reasons students shut down in school, but in my experience, there are two that are especially prevalent. Some kids refuse to try because it’s safer than trying and failing. It’s a form of self-protection. Other kids, especially older ones, who have experienced many years of school already, have picked up cues and messages that they shouldn’t care about schoolwork. Let’s dig into each of these a bit before considering some ways to help these students get out of their own way.

Reason #1: Self-Protection

Students might be avoiding reading or participating in a science group for the same reason I avoid dancing. I would love to be really good at dancing. I see a movie or show with dancing in it, and I think, “I’d love to be able to move like that!” But my self-perception of my abilities as a dancer are pretty low. I’m worried I’ll look foolish, so I avoid dancing when the chance arises. Isn’t this just what happens with a struggling reader or mathematician?

It’s a form of self-protection. A child has experienced repeated failures in a particular subject or task. They’ve tried and failed and tried and failed, and eventually, they start to believe that they’re simply not capable of succeeding. Saying “I don’t care” becomes a defense mechanism.

It’s safer to pretend not to care than to face the pain of failing again. By shutting down and refusing to try, they protect themselves from the emotional toll of failure and perhaps public embarrassment (just like me with dancing). It’s as if they’re saying, “If I don’t try, I can’t fail, and if I can’t fail, I won’t feel bad about myself.”

Reason #2: They’ve Been Taught Not to Care

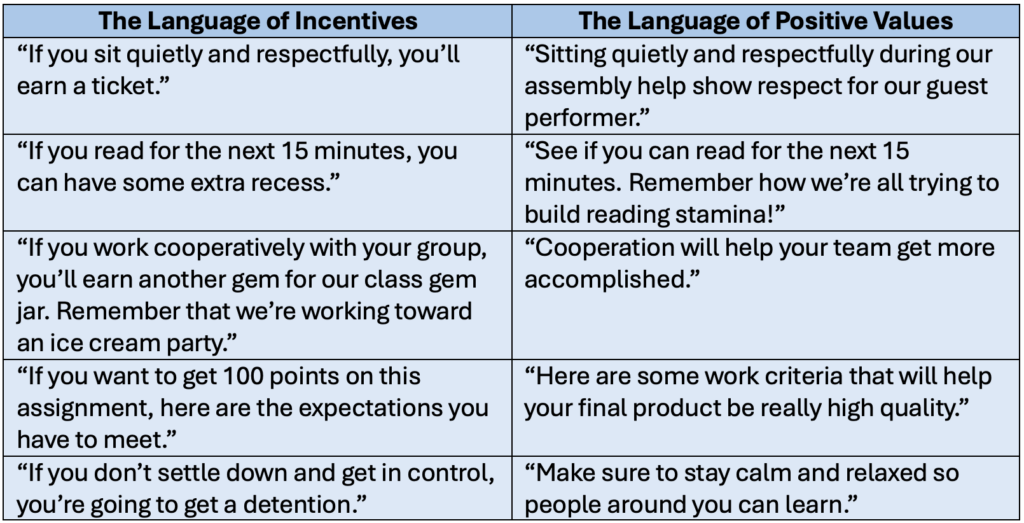

Early on in their school career, when they first started to struggle, some well-meaning adults tried to incentivize their behavior. Perhaps they heard one of these common incentives:

- “If you sit quietly and respectfully, you’ll earn a ticket.”

- “If you read for the next 15 minutes, you can have some extra recess.”

- “If you work cooperatively with your group, you’ll earn another gem for our class gem jar. Remember that we’re working toward an ice cream party.”

As well-intentioned as these incentives may have been, they whisper a troubling underlying message. When we say to kids that they can earn a reward for a behavior, we signal that the behavior is something kids shouldn’t want to do. After all, if the behavior was something they should want to do, why would we bribe them to get them to do it? If reading were inherently pleasurable, why would someone offer them pizza to read over the summer? If someone has to offer pizza to incentivize reading, the message is that reading must be something distasteful.

As students get older, they tend to hear a different set of incentives but still with the same underlying troubling message. In middle and high school, they’re more likely to hear:

- “If you want to get 100 points on this assignment, here are the expectations you have to meet.”

- “If you don’t settle down and get in control, you’re going to get a detention.”

- “If you don’t participate in class, your class participation grade will be low.”

Again, without meaning to, we’re teaching kids that they should only care about doing well if they’ll get something in return. It’s grades or points that matter, not learning or being respectful. If you don’t care about grades or points (or you worry that you won’t get them, even if you try), and that’s what you’re told is the reason for working hard or staying in control, why bother?

Why Should They Care?

Now, we’re left with the question: Why should students care about work or behavior? What values are we trying to help students internalize? This is what we should lead with when we’re messaging the why. Consider these alternatives to the above incentives:

Of course, we know that simply shifting our language won’t have an immediate effect. We won’t be able to just talk about the importance of high-quality work once have kids internalize that value. We’re going to have to do it over and over and over. In my experience as a classroom teacher, it usually took a couple of months of consistency on my part before I started to see significant shifts in students’ attitudes.

Shifting our messaging about values is just one strategy. There are many others we might try when kids are shutting down. Here are a few.

A Few Other Strategies to Try

- Offer Some Choices: Empowerment can often re-engage students. Offer choices in how they approach a task, what topics they explore, or how they can present their learning. Even small choices can give students a sense of control and investment in their work. When choices allow for differentiation, students can choose work that is at their “just right” learning level, which means they can feel competent–which boosts their motivation to work.

- Don’t Engage in Power Struggles: When a student is shutting down, sometimes the best thing you can do is not to engage in a power struggle. Don’t pour energy into convincing them to care—this can reinforce their resistance. Instead, stay calm, express your belief in their abilities, and let them know you’re there when they’re ready.

- Don’t Incentivize: It’s tempting to offer rewards to motivate students, but this can backfire. If students feel they’re being bribed to care, they might become even more resistant. Instead, focus on intrinsic motivation—help them see the personal value in what they’re learning.

- Remind Yourself to Focus on What You Can Control: There are so many factors that go into student engagement. Kids’ prior school experiences, traumas experienced in and out of school, parents’ and family members’ attitudes about learning, and kids’ sleep and eating habits, are just a few variables that we can’t control. So try not to dwell on them. Acknowledge these things and then shift into focusing on what you can (potentially) control: the positive energy you bring to your teaching, your relationship with students, differentiating learning, and other practical strategies.

- Take the Long View: Re-engaging a student who has shut down is not something that will happen overnight. It’s a process that requires patience and persistence. Celebrate small progress and keep your eye on the bigger picture of helping the student rediscover their natural curiosity and desire to learn.

This is hard work, and there’s no simple solution. I’ve offered a few ideas in this post. What else has worked in your experience? How else have you helped kids who appear to not care?

Author

-

Mike Anderson has been an educator for many years. A public school teacher for 15 years, he has also taught preschool, coached swim teams, and taught university graduate level classes. He now works as a consultant providing professional learning for teachers throughout the US and beyond. In 2004, Mike was awarded a national Milken Educator Award, and in 2005 he was a finalist for NH Teacher of the Year. In 2020, he was awarded the Outstanding Educational Leader Award by NHASCD for his work as a consultant. A best-selling author, Mike has written ten books about great teaching and learning. His latest book is Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher. When not working, Mike can be found hanging with his family, tending his perennial gardens, and searching for new running routes around his home in Durham, NH.

- Share:

You may also like

The Perfect Breakfast for Teachers

- February 11, 2025

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference