Beyond Behaviorism: Three Key Strategies

A Brief History of Behaviorism, Part 5

If you could travel back in time about 60 years and walk through a typical school, you might be surprised to find something missing. You wouldn’t see behavior charts or “star student” award posters. You wouldn’t see teachers handing out “cougar bucks” to children walking quietly in hallways or kids being promised pizza if they worked hard during math time. Token economy systems like these hadn’t yet been invented. Have you ever wondered, where did these systems come from?

While writing Tackling the Motivation Crisis: How to Activate Student Learning Without Behavior Charts, Pizza Parties, or Other Hard-to-Quit Incentive Systems, I researched behaviorism, the branch of psychology that birthed these systems. What I learned was fascinating, and it helped me better understand where these incentives systems that are so common (and damaging, by the way) came from. I’m excited to share some of what I learned in this series of blog posts. Enjoy!

Beyond Behaviorism: Three Key Strategies

In the first 4 posts in this series, we explored a brief history of behaviorism—where it came from and how it became so engrained in schools. In this post, we’ll explore what we can do instead.

In Tackling the Motivation Crisis, I outline three key strategies we can implement if we want to move beyond trying to control and/or motivate our students and instead help boost their self-motivation:

- Tap into their intrinsic motivations.

- Reduce (or stop!) using extrinsic motivators.

- Teach students strategies and skills of self-management.

Tap Into Students' Intrinsic Motivations

All students are motivated. They might not always be eager to do schoolwork that’s placed before them, but that doesn’t mean that they want to do nothing. They just don’t want to take a quiz about Chapter 4.

So, one of the keys to student motivation is to tap into the motivations they do have. Here are six that have direct applications in the classroom:

Autonomy: Offer students some power and control over their learning. Let them make some choices about what they learn, how they learn it, and/or how they demonstrate their learning.

Belonging: Help students make connections with each other through their learning. Book clubs, discussion groups, and even simple partner chats are all ways to help students feel a sense of belonging with each other through their academic work.

Competence: It feels good to grow, learn, and be successful. Students should spend most of their academic time in “just right” learning tasks—where they can feel competent.

Purpose: “Why are we doing this?” is a question students ask when they’re seeking purpose. They need to know why they should care about something before they’re willing to invest time and energy in it. We need to be able to answer this question in ways that make sense to them.

Curiosity: When students can spend time learning about things they’re curious about, and when we can introduce students to new topics of interest, learning can flourish. The better we know our students, the better we can find ways to connecting standards and competencies to what students are interested in.

Fun: Like otters, dolphins, and dogs, humans are intelligent social creatures who love to play. When we can incorporate games and playfulness into daily learning, students will be more interested and engaged.

(For a slightly more in-depth explanation of these six intrinsic motivators, check out this article: 6 Intrinsic Motivators to Power Up Your Teaching.)

Before we move on to the second key strategy, there’s an important point to be noted about these six intrinsic motivators. You can also think of them as psychological needs. Your students seek out these qualities all day. When the academic work meets students’ psychological needs, not only will they be more motivated, but they’ll be less likely to try to meet these needs through less productive or disruptive means.

Reduce (Or Stop!) Using Extrinsic Motivators

There’s a whole raft of research from a variety of fields (psychology, sociology, education, and even economics) that shows rewards and incentive systems have all kinds of downsides. They can reduce students’ intrinsic motivation, diminish learning, lower their moral reasoning and academic engagement, and even damage relationships and lower morale. This isn’t just true in the classroom, by the way. The same negative impacts can be seen in nearly all walks of life. (If you’d like to explore some of this research in more depth, check out the “Fascinating Studies and Papers” tab in this LiveBinder.)

So, take down those sticker charts, deemphasize grades as the reason for caring about work, and stop offering pizza parties to incentivize learning. If the work is packed with those six intrinsic motivators, these extrinsic motivators are no longer needed anyway!

This doesn’t mean, by the way, that we have to give up pizza parties and other fun celebrations. Watch a movie every now and then to celebrate the end of an academic unit. Wear pajamas to school to read poetry together. Have a pizza party as a fun treat to celebrate your class community. We can still enjoy these kinds of things with our students–we just shouldn’t dangle them as the carrot to motivate their behavior or work.

Teach Students Strategies and Skills of Self-Motivation and Self-Management

Being motivated isn’t enough. You can really want to run a marathon, but if you can’t make yourself lace up your sneakers and put in the hard work on the road, you’re never going to get there. A student can really want to learn a lot about birds and can initially be fired up for their research project, but without skills and strategies to help them keep moving forward, especially when the going gets rough, they’re probably not going to be successful.

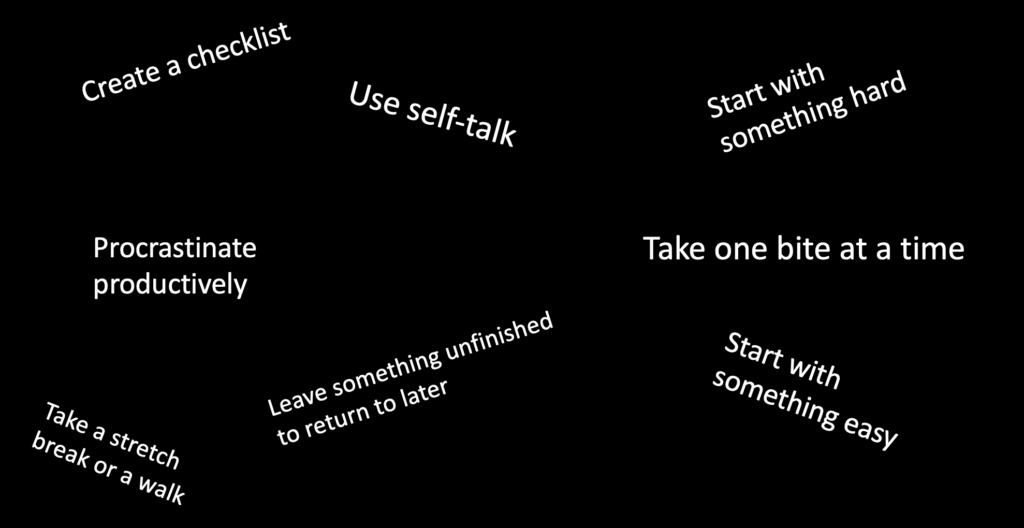

This might feel overwhelming. Where do you start? You might begin by thinking of the strategies you use yourself. How do you force yourself to push through challenges? How do you keep yourself from getting overwhelmed when you’re in the midst of an overwhelming project?

Here are a few strategies to get you started.

We’ve come a long way in our understanding of human motivation. Behaviorism (which still has a place in very specific and limited applications, I think) was never intended for widespread use in schools. And its overuse is having serious negative consequences on children’s learning and motivation.

Want to change the paradigm? Tap into students’ intrinsic motivations. Stop incentivizing learning and behavior. Teach students the strategies and skills they need to self-manage and be self-motivated. It’s harder, no doubt, than using tickets or marbles or grades…but it will set your students up for success in the long run.

3 Strategies to help students be more self motivated: 1. Tap into intrinsic motivation. 2. Stop incentivizing learning and behavior. 3. Teach students the skills they need to self-manage and be self-motivated.

Mike Anderson Tweet

Have you read this whole series?

Here is an easy go-to list of all of the posts in this series:

Part 1: Drooling Dogs and the Birth of Behaviorism

Part 2: BF Skinner and Token Economy Systems

Part 3: What If There’s More to Behavior than Behaviors?

Are you interested in learning more about how to move away from incentives? Here are three resources to check out.

This free LiveBinder is packed with practical resources: articles, videos, research studies, and more!

In this online course for K-12 educators, I offer many practical ideas and strategies for fostering students’ self-motivation in the classroom.

You might also check out my book, Tackling the Motivation Crisis!

Author

-

Mike Anderson has been an educator for many years. A public school teacher for 15 years, he has also taught preschool, coached swim teams, and taught university graduate level classes. He now works as a consultant providing professional learning for teachers throughout the US and beyond. In 2004, Mike was awarded a national Milken Educator Award, and in 2005 he was a finalist for NH Teacher of the Year. In 2020, he was awarded the Outstanding Educational Leader Award by NHASCD for his work as a consultant. A best-selling author, Mike has written ten books about great teaching and learning. His latest book is Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher. When not working, Mike can be found hanging with his family, tending his perennial gardens, and searching for new running routes around his home in Durham, NH.

You may also like

The Perfect Breakfast for Teachers

- February 11, 2025

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference