Square Pegs and Round Holes: Why I Moved Away From Letter Grades

Square pegs and round holes. This phrase plays over and over in my head each time I try to assign a letter grade to my students at the end of a marking period. My students’ learning is so complex, and a letter grade is just so superficial and limiting. The two are simply not compatible in my mind. Thus, the wrong shaped peg (a letter) for the hole (accurate reflections of student learning and growth).

Trying to sum up the learning my students did in an entire marking period with one letter seemed virtually impossible; yet, kids and parents hung on every point that led to that final grade. Students and parents almost never told me that they were concerned that they missed learning, but rather parent communication almost always revolved around concern about an assignment that was worth points. Something needed to change. I wanted my students and their parents to recognize and focus on the importance of the learning and not the “game” of points and grades. I also know that parents are concerned with learning; it’s just that the traditional system we have all grown accustomed to, uses the language of grades and a certain level of a transaction of work for grades.

Therefore, this year, in my middle school Literacy Support classes, I decided to replace my letter grades with something else. I wasn’t actually sure what that something else was going to look like, but I knew what I wanted to achieve philosophically. I had to start somewhere; so I started with something I did know.

I knew for sure that I wanted to communicate information about learning and student progress toward mastery of skills and subsequent standards in a meaningful way. I did know that I wanted to encourage student ownership and reflection. What I didn’t yet know was how I was going to handle the logistics and messaging that would be necessary to achieve this goal.

I started with several very frank discussions with students about the difference between learning and grades. I asked questions like, “Have you ever gotten a good grade even though you didn’t work hard?” Or, “Did you ever get a ‘not so good’ grade even though you worked really hard? Why is this?” Students were so insightful, and reflective. They knew the difference and recognized that grades don’t necessarily reflect the amount of learning they did in class.

After getting their input, I worked to develop an alternative system for this philosophy of communicating progress, and came up with a document that required students to continually monitor, rate, and reflect upon where they were with regard to selected skill mastery and progress.

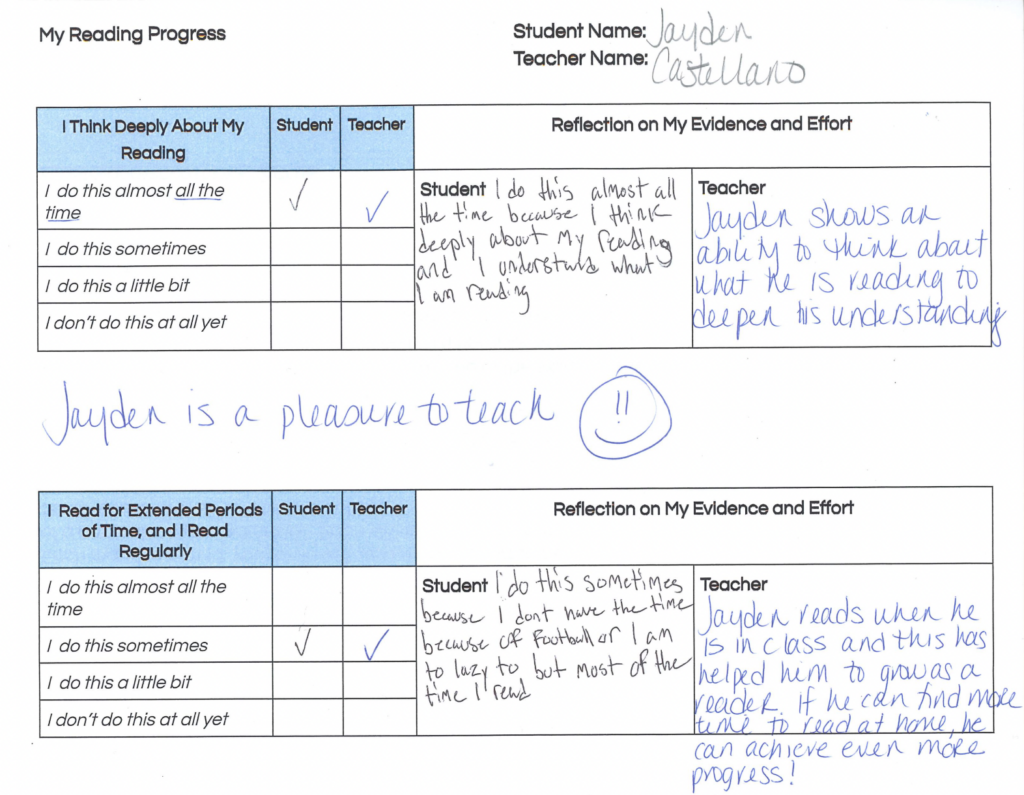

Students rated their progress relative to a goal by selecting one of four choices: I do this almost all the time, I do this sometimes, I do this a little bit, I don’t do this at all yet. The language of this document was particularly important, in that I wanted it to belong to students, and not to me. It was also important that the language indicated what they do and do not do, and not what they can and cannot do. This language is meant to reflect a growth mindset.

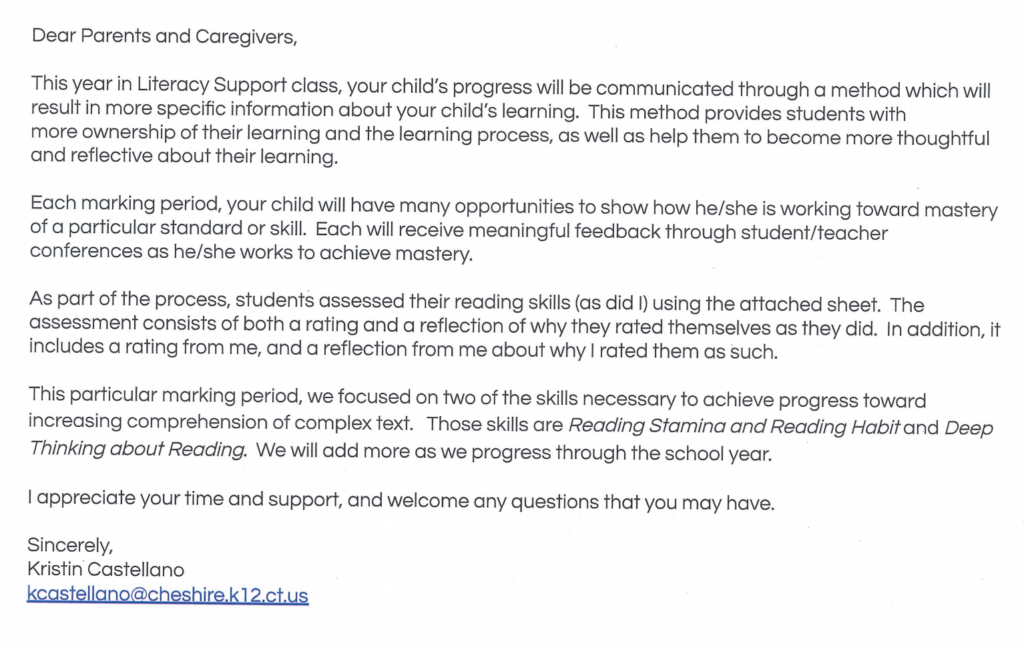

After continually returning to the document to self-assess using evidence from in-class work, students came to see the process as a regular way to determine their growth relative to a skill. They became more and more accustomed to using evidence from their work to show that they had grown as readers. At the end of the marking period, each student participated in a short student-teacher conference where the students explained their ratings and showed evidence to support those ratings. In addition, they reflected upon why they rated themselves as they did. I did the same. The whole conversation and process revolved around learning, with no mention of a letter grade. With students’ final approval, these documents (below) were scanned and emailed home to parents and guardians in lieu of a letter grade.

In this way, each student was sure of the skill development that had occurred and where they stood in relation to mastery of that skill. More importantly, the students owned the process. They became invested in showing evidence of their growth. This made buy-in of daily learning experiences much easier. These students were motivated more intrinsically. I didn’t have to offer lollipops or pizza parties to get them to read; most did it because they were invested.

I have received quite a few emails from parents that have been useful in initiating dialogue about progress. In the past, the emails I received at the end of a marking period were about “the grades.” My most recent email conversations have been about learning. I half-expected push back, because no letter grade was assigned to the class; instead I received many responses with thanks for the helpful feedback.

Perhaps I am getting closer to finding a better fitting peg to fit the hole.

Author

-

Kristin Castellano has been a teacher at Dodd Middle School in Cheshire, Connecticut for 29 years. She teaches Literacy Support and Multi-Language Learners and serves as Division Leader. She has participated in curriculum writing and led professional development sessions on topics like literacy across the curriculum and creating a culture of reading in middle school. She also received the honor of being named Teacher of the Year in Cheshire in 2018. She feels that the best part of working with striving readers is finding that one book that takes a student from being a non-reader, to one who enjoys reading. In addition to teaching, she loves to travel to gain new perspectives on life in other cultures.

You may also like

The Perfect Breakfast for Teachers

- February 11, 2025

- by Mike Anderson

- in Blog

Finding Time for a One-on-One Problem-Solving Conference